Health care consumers are contributing their skills, money, and time to develop effective solutions that aren’t available on the commercial market.

This article is published under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 and can be freely copied and distributed without permission.

Patients are increasingly able to conceive and develop sophisticated medical devices and services to meet their own needs — often without any help from companies that produce or sell medical products. This “free” patient-driven innovation process enables them to benefit from important advances that are not commercially available. Patient innovation also can provide benefits to companies that produce and sell medical devices and services. For them, patient do-it-yourself efforts can be free R&D that informs and amplifies in-house development efforts.

In this article, we will look at two examples of free innovation in the medical field — one for managing type 1 diabetes and the other for managing Crohn’s disease. We will set these cases within the context of the broader free innovation movement that has been gaining momentum in an array of industries1 and apply the general lessons of free innovation to the specific circumstances of medical innovation by patients.

Example 1: Managing Type 1 Diabetes

In 2013, Dana Lewis, a professional in health communications in her 20s, joined forces with a software engineer and a few other individuals with type 1 diabetes to develop for themselves what the medical device industry had been promising to deliver for decades: an artificial pancreas. As patients, they sought to solve the problem of low overnight blood sugar levels, a common occurrence that can be deadly. They wanted to design a system that could automatically monitor blood sugar levels every few minutes and provide the right insulin dose to keep the number in a healthy range.

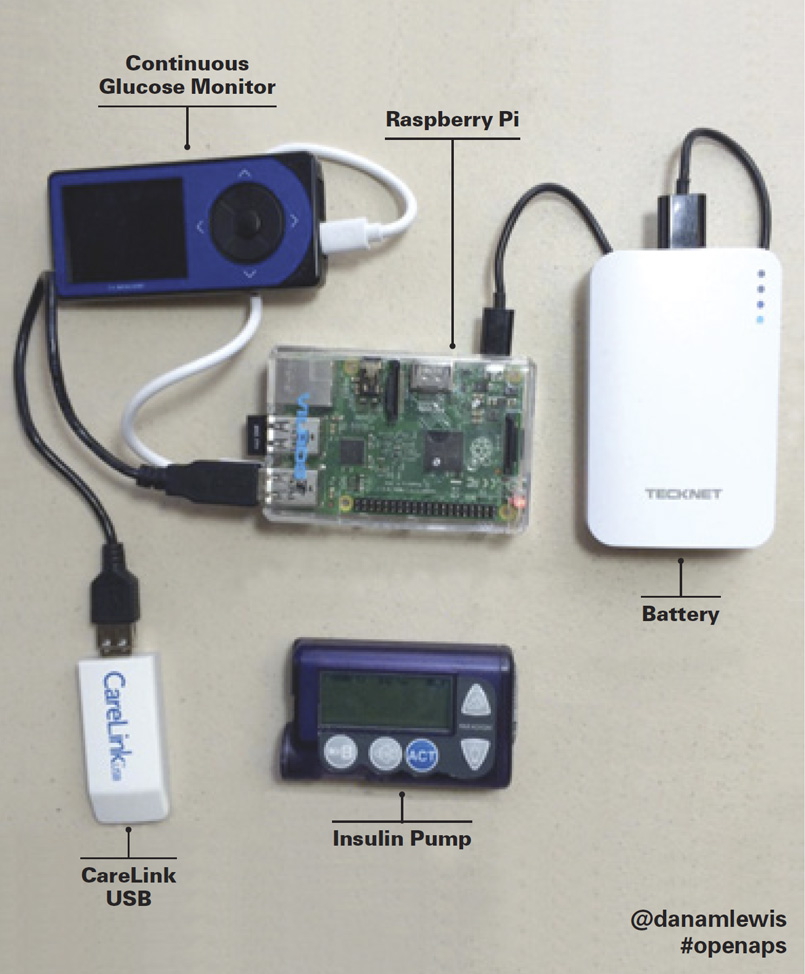

Within months, Lewis and her coinn ovators designed an artificial pancreas that used computer code they wrote themselves and off-the-shelf hardware to connect commercially available continuous glucose monitors with commercially available insulin pumps. The device significantly improved Lewis’s ability to manage her own blood sugar levels. She and her colleagues decided to make the design available to others online and make their software open source. This was the start of the Open Artificial Pancreas System (OpenAPS) movement.2 Today, multiple communities participate in this movement, multiple noncommercial DIY artificial pancreas designs are being shared, and thousands of individuals with diabetes use these DIY systems daily to monitor, manage, and improve their health.

ovators designed an artificial pancreas that used computer code they wrote themselves and off-the-shelf hardware to connect commercially available continuous glucose monitors with commercially available insulin pumps. The device significantly improved Lewis’s ability to manage her own blood sugar levels. She and her colleagues decided to make the design available to others online and make their software open source. This was the start of the Open Artificial Pancreas System (OpenAPS) movement.2 Today, multiple communities participate in this movement, multiple noncommercial DIY artificial pancreas designs are being shared, and thousands of individuals with diabetes use these DIY systems daily to monitor, manage, and improve their health.

Example 2: Managing Crohn’s Disease

Sean Ahrens, a computer science and business graduate from the University of California, Berkeley, became frustrated in his early 20s that there wasn’t any detailed medical information on what he could do to minimize debilitating flare-ups from Crohn’s disease. Although several drug treatments for Crohn’s existed, all of them had significant toxicities and none was effective for every patient. As a result, many people tried to manage and reduce their symptoms through dietary choices. To fill a resource gap for patients, Ahrens, who was diagnosed with Crohn’s when he was 12, created a website in 2011 called Crohnology, where fellow patients were invited to share their experiences regarding interventions and outcomes through an online questionnaire. The site compiled the data so that everyone could see which factors others found troublesome and which were helpful.3Today, the site has more than 10,000 registered users. Crohn’s patients throughout the world have come to find the information invaluable for managing their chronic disease.

The General Practice of Free Consumer Innovation

What is striking about both of these cases is that neither commercial medical producers nor the clinical care system offered a solution that these patients urgently needed. Motivated patients stepped forward to develop solutions for themselves, entirely without commercial support.4

Free innovation in the medical field follows the general pattern seen in many other areas, including crafts, sporting goods, home and garden equipment, pet products, and apparel.5 Enabled by technology, social media, and a keen desire to find solutions aligned with their own needs, consumers of all kinds are designing new products for themselves. (See “About the Research.”)

Consumers innovate and diffuse their innovations in ways that are very different from producers, and it is important to understand the differences. (See “Consumer Versus Producer Innovation.”) Unlike traditional producers, who start with market research and R&D, free innovation begins with consumers identifying something they need or want that is not available in the marketplace. To address this, they invest their own funds, expertise, and free time to create a solution. Rather than seeking to protect their designs from imitators, as commercial innovators do, we found that more than 90% of consumer innovators make their designs available to everyone for free. What’s more, they let other people test and improve on the initial design and make the new version available for free as well. Once a design is fully developed, it gets diffused still further, allowing consumers to make their own noncommercial copies, and allowing producers to commercialize the designs without having to license them from the consumer innovators.6

You might wonder why individuals would bother to invest time and money in innovations without any expectation of being paid for either their labor or their product designs. The answer is simple: Consumers who innovate are attracted by the personal benefits, such as the opportunity to use their innovations and the fun and learning they gain from the process of developing them. They also get satisfaction from sharing their innovations with people with similar needs.7 In other words, they are self-rewarded.

As different as the consumer and commercial paradigms are from each other, they are complementary rather than opposing. Indeed, research shows that consumers, producers, and society at large are best served when both paradigms are used simultaneously.8 Producers can benefit from consumer innovation by adopting consumer product designs developed and tested by consumers for free; consumers benefit from producer-developed modules for DIY projects such as Raspberry Pi microcomputers and also from producer-developed innovations that serve mainstream needs. And, of course, society as a whole benefits when consumer and producer innovators focus on what they do best and most efficiently.9

Applying the Ideas of Consumer Innovation to Health Care

Surveys show that medical-device development by patients is taking place on a massive scale. In nationally representative surveys conducted from 2010 to 2015 in the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, Finland, Canada, and South Korea, approximately 1 million individuals reported that they had developed medical innovations to serve their own needs in the three years preceding the surveys.10 Although the basic practices underlying free consumer innovation apply across sectors, innovators must make adaptations for their own personal and market environments. In the case of patient innovation, the most important adaptations have to do with ensuring safety and supporting free diffusion.

When a medical product that meets patient needs is available on the market, patients often prefer to buy that product rather than developing their own or copying another patient’s free design. However, if a solution isn’t available commercially and the need is urgent, many try to design and build their own product. Things patients need may not be profitable to produce for reasons including the following:

- Thousands of rare diseases are chronic and challenging for patients to manage on a long-term basis. In many instances, the diseases afflict relatively few patients and represent markets that are too small for producers to profitably serve.

- Often, even when a large number of patients have the same need, producers don’t have sufficient incentive to innovate because there’s no good way for them to profit from the type of solution that’s needed. Crohn’s disease offers a case in point. As useful as it may be for Crohn’s patients to manage and reduce their symptoms through diet, getting companies to invest in the clinical trials is a hard sell. They would want to recoup the costs via patented food products or other measures.

- Even if an innovation can be protected and is potentially profitable, the regulations governing clinical trials tend to make it costly and slow for producers to get approvals. For example, in the United States, getting Food and Drug Administration approval for a device of low or moderate risk takes an average of 10 months. Approvals for high-risk devices — such as an artificial pancreas — could take four to five years and cost $75 million.11 As demonstrated by the history of the patient-developed artificial pancreas, patient innovators (whose noncommercial activities are exempt from FDA regulation) may be able to develop and produce something in a matter of weeks or months, at very little cost.

One or more of these constraints can inhibit the commercial provision of many things that patients need. This makes the free patient innovation system a critical resource that must be recognized and supported